Food for Thought – Misogyny, Feminism, and Gender

“Are you a Feminist?”

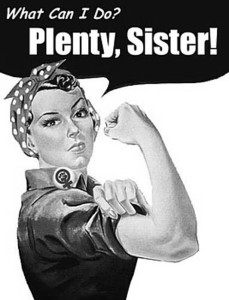

In my first year at Cambridge, two passionate and outspoken self-declared feminists put me on the spot. I was anxious because I knew that my answer was going to be “no” despite the fact that they had both given great speeches on gender inequality and the need for change – something I wholeheartedly agreed with. My qualms with the F-word and the reason why I did  notidentify as a feminist was because I did not actually know what feminism meant. I thought that calling myself a feminist meant either being an angry man-hater, a radical hippie political activist, or simply being irrelevant in an age where women can vote. At this stage, I was still finding my place in the world (of Cambridge), wary of peoples’ perceptions, and just wanting to be neutral.

notidentify as a feminist was because I did not actually know what feminism meant. I thought that calling myself a feminist meant either being an angry man-hater, a radical hippie political activist, or simply being irrelevant in an age where women can vote. At this stage, I was still finding my place in the world (of Cambridge), wary of peoples’ perceptions, and just wanting to be neutral.

In this article, I would like to share my Cambridge journey, guide you through my thoughts and explain why I am where I am now – why I do now call myself a feminist and why I want to open this dialogue amongst the Malaysian community here. My opinions have been shaped by discussions and debates with family, friends, and strangers; my geography course; worthwhile procrastination on the CUSU Women’s Campaign Facebook discussion group and Oxford’s equivalent; and a narrow escape from assault in front of my own home. Throughout these three years, my thoughts on gender equality have not changed – all humans are still and will always be equal – but my thoughts on how to achieve equality and on how to be aware of gender sensitivities have. I do not claim to have the answers nor do I claim to have finished my own journey of discovery. I am sharing with you some of my thoughts-in-progress and I want to continue the discussion with you. Essentially, I aim to open a space where the Malaysian community here can explore gender and gender-related issues.

It does not mean I hate men

In case you are wondering whether men can be feminists too, and so that I do not already lose half my potential readership, one of the feminists who asked me if I was a feminist is a man. Feminism does not hate men. Being a feminist also does not mean that I am blind to problems facing men or other marginalised groups such as LGBT+. All of these oppressions are interlinked. There are many feminisms and many ways of doing and thinking all of these feminisms. It took me a while to understand this, particularly because many feminists advocate a sort of Feminism 101 that excludes you from being a feminist if you do not agree with them on all of their ‘policies’. This is all the more why I do not want my opinions to be prescriptive. Disagreements amongst feminists touch on many issues including the extent to which men should be included in feminist movements, which ‘battles’ need to be fought, the merits of a no-platform policy, the importance of safe spaces and trigger warnings, how this all relates to religious beliefs, or whether there even are many feminisms. I am aware that I have just opened up a huge range of massive issues; I am still navigating through all of these myself. My point is that we need to talk about them as a community – not necessarily to find all the correct answers but to understand our respective experiences and to create a culture of empathy.

It does not mean I am a radical hippy

Three years ago, I shunned away from anything remotely political. I did not want to talk about feminism, partly for fear of being branded as political and partly because I thought I knew nothing about politics. Although there is nothing inherently wrong with being a hippy or radical or a political activist, there are certainly negative connotations attached to all of these identities that many are afraid of. I completely understand that. I am so grateful to CUMaS and particularly Low Wen Zhen for providing me a turning point in a few poignant lines of the MNight 2012 Amnesia script:

Marcus: I mean, this is political. Very political. I don’t know, but I don’t want to get involved in politics. It’s dirty.

Nadia: Dirty?

Marcus: Dirty. Oh yes. You don’t want to know how dirty it gets in 2012. [shudders] No, you don’t.

Ah Huat: Everything also political what, right?

Wai Foong: Yes, every aspect of our lives is affected by politics. What we learn. How much we earn. What we do for a living. What we read and listen to.

Uncle Sim: I see no reason why you should fear politics, Marcus. Politics is about people. About people making decisions together to reach the best decision for everyone. Politics is all about improving the human self. It has always been a noble cause.

(Amnesia, Act 2 Scene 3)

Feminism stands for equality. It is not extreme/stupid/naïve/dirty/right- or left-wing to believe that everyone, irrespective of gender, is equal. It is not extreme to believe that all genders should be paid equally for doing the same job. It is not extreme to believe that all genders should have equal access to clean water, sanitation, education, legal aid, food security, medical treatment, political representation, the labour market, or even citizenship. It is not extreme to talk about gender equality.

It does not mean I am irrelevant

Even though women can now vote in many countries, we see discrimination against women everywhere on an everyday basis, whether in Malaysia, in the UK or anywhere else in the world. Malaysian school textbooks perpetuate gender stereotypes (Abdul Hamid et al. 2008). By preferentially depicting males, pupils are led to believe that males are the norm in society. Female role assignments are subservient, involving non-remunerated tasks around the home such as domestic chores while their male counterparts are assigned a wide range of remunerated occupations and depicted as problem-solvers and independent leaders. You may think it is just a book, but this is what the kids in our country are learning and it does have very real repercussions. When Malaysian Roshini Muniam Rose reached the finals of an astronaut competition, standing against four men, she received sexist abuse telling her that not only she was ruining what is intended to be a man’s job but also that, as a woman, she was physically incapable of being an astronaut.

Roshini’s example is not an isolated case of sexism. The 90% male House of Parliament is known to be a stage for particularly sexist and derogatory remarks. The Cabinet is 94% male. Does this representation really put the population’s best interests forward? In 2009, the director-general of the Labour Department ridiculed the need for a Sexual Harassment Act, saying it “could lead to a dull and rigid environment in the workplace”. Large numbers of women, disproportionately to men, are coerced into the sex trade and are victims of human trafficking, of which Malaysia is a known hub. Malaysian law too narrowly defines rape as the penile penetration of the vagina without the woman’s consent. Laws such as the Domestic Violence Act 1994 do not criminalise wife-beating or marital rape. The Federal Constitution does not allow women the same rights as men regarding citizenship status of foreign spouses or even their own children if the child is born outside of Malaysia. Section 498 of the Penal Code allows a husband to sue another man for “enticing” his wife. Not only does this infer that a married woman is unable to think for herself but it equates her to the husband’s sexual property. Finally, no discussion on Malaysian discrimination is complete without bringing up race and ethnicity. Many of you will have read the eloquent articles by CUMaS’ own Julian Tan, calling for a more accountable and just Malaysia, rid of institutionalised racism and that fundamentally loves all its people. Sexism compounds racial issues. Victims of racial discrimination in employment and education are disproportionately women.

Feminism is relevant for all of us. Indeed, there is so much literature and so many statistics available that I could have gone on for a long time. Intellectually, it is easy to appreciate this, but often it is a personal experience (or that of a friend or acquaintance) that makes us truly understand what is so wrong about our society and spurs us to action. On the 1st January 2013, New Year’s Day of my second year, I fully understood this. After being threatened by three men in what I had previously considered to be a safe space, I became tragically aware of my female body and have since been insecure about it. By amazing luck and grace, I managed to escape physically unharmed but of course in these situations you always imagine the worst that could have happened. I still find it traumatising to walk alone at night and find myself rearranging my plans such that I never need to. Many will tell me that I am being irrational or overly emotional, that the worst did not happen. But the point is that I feel fear because of the politics of my female body. Most men never have to deal with this; most women do. Often I replay what happened that night, analysing what I did or did not do, what I said or did not say. I keep coming to the same conclusion: I did not do or say anything wrong. In fact, I think I did everything right and handled the situation perfectly. But what if I had been wearing a short skirt? What if I had known this would likely happen yet still wanted to go home? What if I had not run the very moment I did? Would it then have been my fault? Sadly, many would think so – and that is exactly what has got to change.

How can we change this?

In the grand scheme of things, we are tiny. As one of my supervisors once put it, we are simply ants crawling around Planet Earth. Especially as students, we do not have much say on all the aforementioned issues. Especially as a woman, I do not have much say on all the aforementioned issues. This is all pretty demotivating but there is so much that we can do in our everyday lives to gradually change the situation – scroll back up and read that excerpt from Amnesia again in case you have already forgotten it. Politics is everyday.

Firstly, we need to be mindful of gender subjectivities and of our own privileges. Guys, not sure what your male privileges are? Being unaware of your male privilege is probably the ultimate example of male privilege. This checklist of male privileges is your first stop to understanding what I am talking about. Please do not apologise for these – I know they are not your fault – but you need to be aware of the implications they have for your relations with others who have different privileges.

Secondly, we need more gender awareness in our own language and behaviour to avoid stereotypes and myth-perpetuation. Do not question a woman’s decision to focus on her career if you are not going to question the same of a man. Do not ask how a successful businesswoman can juggle her career whilst also being a wife and mother-of-three if you are not going to ask the same of a man (his answer might be that his wife is doing the domestic work for him). Do not make sexist jokes. They are never funny.

Thirdly, we need to call people out when they are intentionally or unintentionally sexist. This does not mean simply calling people sexist and refusing to engage in further discussion because you are offended. We need more discussion, we need to inform people who may never have come across such issues, and we need to apologise when we are called out. This whole process does not have to be antagonistic. This very article is the fruit of an unintentional yet unfortunate situation that I think has created positives for all involved and hopefully also for the wider Malaysian community here in Cambridge.

We are all going to be leaders one day and some of you already are. Whether you are leading CUMaS, a private company, a political organisation, a research unit, your own kids, or your neighbour who thinks you have incredible fashion sense, we all have the opportunity to create change. On that note, I end with a question to you: are you a feminist?